Rhode Island Slave History Medallions

Biography of Peter Quire

Compiled and written by Imen Boussayoud, PhD Candidate

Department of History | Brown University

Throughout his life, Peter Quire demonstrated a dedication to Black liberation and community building across the Northeast. Peter was born on June 15th, 1806 in Pennsylvania. As a young man, he worked as a driver for Dr. Joseph Parrish in Philadelphia. Parrish was a prominent Quaker figure in the region, and was, for years, the president of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery. The Parrish family basement was a stop on the Underground Railroad, housing a hiding space for escaped enslaved people until they were able to move to the next safe house. Peter Quire worked on these rescue missions, chasing down would-be slave catchers in Parrish’ carriage and rescuing the people they sought to traffic into slavery. Joseph Parrish’s granddaughter, Susanna Parrish Wharton wrote that “By active efforts he [Peter] was often able to release slaves unlawfully seized.” 1

Though Peter stayed in communication with the Parishes over the years, this did not mean that they viewed the relationship as one between equals. We know little else of Peter’s efforts in freeing enslaved people, as the Parrish family’s writings focus almost exclusively on the actions of Joseph Parrish. About her grandfather, Susanna Parrish Wharton wrote, “I have been told by a friend who was present that when my grandfather died, the sidewalk was filled for two squares with negroes walking in the funeral procession. It is easy to understand why from childhood my mother openly espoused the cause of this race.” 2

The Parrish family, like many Quakers, did not center Black Americans in their abolitionist endeavors, but rather on themselves for helping them in their plight. Many Quakers saw their relationship to Black Americans as a paternalistic one, in which it was their divine responsibility to stop the sin of slavery from bringing the wrath of God down upon them. Despite this however, Quaker political, economic, and legal support was a lifeline to many enslaved and free Black Americans, who otherwise faced structural

barriers to that support. 3

After his work on the Underground Railroad, Peter became a shoemaker in Chester, Pennsylvania and married a woman named Maria Quire. 4 By 1831, they received a plot of land in Timbuctoo, New Jersey from another prominent Quaker household, the Atkinsons. 5 Timbuctoo was a settlement of free Black people in Burlington County, New Jersey. Likely founded between 1820 and 1830, the community was small for the first few decades, having around 125 residents by 1860. The origins of its name remain

unclear. It may have been a signal for the free Black community to draw in other Black residents, or a racist label for the town from its white neighbors in Mt. Holly. 6

It is quite likely that Peter and Maria acquired this plot of land through their Quaker connections. Burlington, New Jersey had long been a hub for the Quaker population, and Joseph Parrish was a highly influential figure in the county. 7 The plots of land Quakers sold, or on occasion donated, to Black people in Timbuctoo was often not enough to build self-sufficient farms on. This may explain why Peter and Maria continued to live across the river in Pennsylvania.

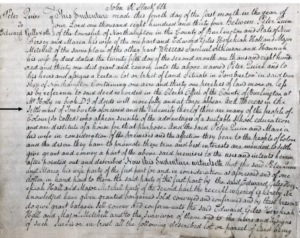

Nonetheless, Peter and Maria did something noteworthy with this land. On January 4th, 1834, Peter and Maria Quire sold part of their plot for $1 to a man named Edward Giles in order to build a school for Black residents. The deed says as follows,

“And whereas in the settlement of Tombuctoo [Timbuctoo] aforesaid and the Vicinity thereof there are many of the people of Colour (so called) who appear sensible of the advantages of a suitable school education and are destitute of a house for that purpose. And the said Peter and Maria his wife in consideration of the premises and the affection they bear to the people of colour and the desire they have to promote there [their] true and best interests are minded to settle give grant and convey a part of the above said premises to the uses and interests herein after pointed out and described.” 8

Peter and Maria Quire recognized schooling as an essential need for this small, Black, emancipated community growing in Antebellum New Jersey,. They continue to demonstrate their care for the community by specifying in the deed that all board members for the school must be ‘People of Colour’ who live within 10 miles of the property. 9 While Peter continued a relationship with the Parrish family throughout his life, this part of the deed shows that he and Maria were, at the least, skeptical of Quakers’

relationship with their Black neighbors. Despite how well-meaning white Quakers were, Peter and Maria did not want them in charge of the education of Black children. Peter and Maria’s deed, written more than three decades before the onset of the Civil War, sought to ensure that Black residents maintained self-determination over the schooling of their community.

Peter lived in Pennsylvania with Maria until at least 1850. We lose track of Maria here, and it is possible that she may have passed away, as in the 1865 census, Peter is listed as living in Newport, married to a woman named Sarah. 10 It is possible that Peter utilized more of his Quaker connections to move to Newport, as they had a strong presence in the area. By 1870, Sarah had passed away and Peter was married to Harriet Frances Rodman Quire. 11 Harriet had been baptized at Trinity Church, and was likely a longtime churchgoer. 12 Following their marriage, Both Peter and Harriet became active members of Trinity Church, receiving communion there. 13 This was outside of the norm, as many Black Rhode Islanders refused to go to churches in the state. Nearly all Rhode Island churches were segregated, forcing Black worshippers to sit in ‘pigeonholes’. These pews were purposely out of the line of sight of white churchgoers. 14 At the time that

Peter and Harriet went to Trinity, there was one Black church in Newport, the African Union Meeting House, founded in 1822.

Five decades later, in 1875, Peter and Harriet invited the rector of Trinity Church and several other members of the community to meet for worship in their home. For the next seven months, Peter and Harriet hosted services above Peter’s cobbler shop on Third and Poplar Street in Newport. Their storefront and home was located in the Point, a Newport neighborhood which was home to sailors, immigrants, and free Black residents. 15

As their congregation grew, so did their need for space. Peter, Harriet, and those who came weekly to worship in their home pulled from their relationships within the Point and Newport as a whole to crowdsource donations, labor, and equipment. Later that year, they built St. John’s Church, a small wooden structure further down on Poplar Street. This building remains in use to this day as St. Johns’

Guild Hall. In welcoming those of all races to worship at its pews, St. John’s became a valuable space of spiritual community for Rhode Islanders.

Harriet Frances Quire passed away on April 10th, 1883. Fittingly, hers was the first funeral held at St. Johns. Two years after Harriet’s death, St. John’s was accepted into the Episcopal Diocese of Rhode Island. It did not put itself forward to receive funds from the Diocese, likely meaning that it continued to be self-funded by itself and the community. 16 Upon his death in 1899, Peter Quire bequeathed his life savings of $419 to St. John’s Church. 17 Adjusted for inflation, this is the equivalent of nearly $14,000 in

2024. Peter Quire’s life is a remarkable one. He was a young carriage driver that raced through the streets of Pennsylvania to save enslaved people, gave land with his first wife Maria to start a free Black school in Antebellum New Jersey, and alongside Harriet, founded St. John’s Church in Newport. Peter and Harriet’s legacy stands to this day, with St. John’s continuing to promote the wellbeing of its racially diverse congregation.

Source: Burlington County, NJ, Deeds, G3:389, Peter Quire to Edward Giles, et al, (January 4, 1834) Burlington County Clerk’s Office, Mount Holly in Weston, Guy. “Timbuctoo and the First Emancipation of the Early-Nineteenth Century.” New Jersey Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 8, no. 1 (January 27, 2022): 224–59.

1 Parrish, Dillwyn. The Parrish Family. (G. H. Buchanan Company, 1925.), 258.

2 Wharton, Susanna Dillyn. Friends Intelligencer, Philadelphia, September 25, 1913, Number 39.

3 There were still some outliers in the Quaker community who owned slaves. In New Jersey, they

comprised 3% of the total slaveowning population. Weston, Guy. “Timbuctoo and the First Emancipation

of the Early-Nineteenth Century.” New Jersey Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 8, no. 1 (January 27,

2022): 224–59.

4 The National Archives in Washington D.C.; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census;

Record Group Number: 29; Series Number: M432; Residence Date: 1850; Home in 1850: Sadsburyville,

Chester, Pennsylvania; Roll: 766; Page: 302b

5 Burlington County, New Jersey, Deeds, G3:389, Peter Quire to Edward Giles, et al (January 4,

1834),Burlington County Clerk’s Office, Mount Holly.

6 Barton, 31.

7 Proceedings of a Complimentary Dinner Given to Dr. Joseph Parrish of Burlington, N.J. Press of the

Case, Lockwood & Brainard Company, 1890.

8 Burlington County, New Jersey, Deeds, G3:389, Peter Quire to Edward Giles, et al (January4,

1834),Burlington County Clerk’s Office, Mount Holly

9 Ibid.

10 Rhode Island State Census, 1875. Microfilm. New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston,

Massachusetts. Accessed via Ancestry, Rhode Island, U.S., State Censuses, 1865-1935 [database on-

line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013.

11 1870 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc.,

2009.

12 Arnold, James Newell. Rhode Island Vital Extracts, 1636–1850. (Providence, R.I.: Narragansett

Historical Publishing Company, 1891–1912), pg 523. Digitized images from New England Historic

Genealogical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

13 Merolla, James. “St. John the Evangelist – The Legacy of Peter Quire – Newport This Week.” Newport

This Week -, September 3, 2015.

14 William J. Brown, The Life of William J. Brown (Providence, RI: Angell and Printers, 1883), pg. 46-47.

15 Newport History: Bulletin of the Newport Historical Society. (Volume 159, United States: The Society,

1973) 336-342.

16 Journal of the 95th Annual Convention, Diocese of Rhode Island. United States: The Diocese, 1881, pg

17.

17 Merolla.