Slavery in Barrington, Rhode Island

Written by Stephen Venuti, President of Barrington Preservation Society

Edited by Charlotte Carrington-Farmer, Associate Professor of History, Roger Williams University

October 2022

The history of enslavement in Barrington spanned a period of nearly two hundred years and predates the establishment of the town itself. By the 1670s, enslaved peoples were present in several prominent households within the Sowams area, including what is now the modern-day town of Barrington. This included the Willett, Myles, and Browne family homes.

At the time of his death in 1674, Thomas Willett left “eight negroes” with a total assessed value of £200 to his wife and children. In the midst of King Philip’s War, enslaved peoples lost their lives, including an unnamed man enslaved by the Reverend John Myles. Jethro, who was enslaved by the Willett family, was taken into captivity, but eventually escaped. After being returned to his enslavers, Jethro eventually got his freedom two years later for warning of an imminent attack on the town of Taunton during the war. In the aftermath of the war, Indigenous Peoples were sold into slavery, not only here throughout New England, but around the Atlantic World.

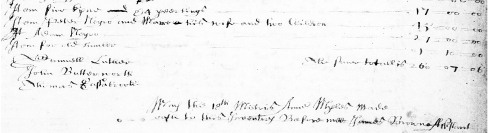

The Inventory from the Will of Rev. John Myles, dated 1682, listing five negro slaves: Peter, his wife Mary and their two children – valued at £45.00, and Adam – valued at £27.00

Estate inventories from the late seventeenth century reveal the continued presence of enslaved peoples in Barrington. When Reverend John Myles died in 1683, he left behind five enslaved peoples, including Adam, who was valued at £27. The Myles family inventory reveals the reality of child slavery, as in addition to enslaving Peter and his wife Mary, the family also enslaved their two unnamed children.

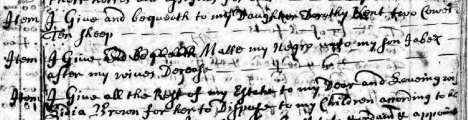

When James Browne died in 1694, he bequeathed “Matte my negro unto my son Jabez” upon the death of his wife, Lydia. Lydia’s will, dated 1710, listed “one negro man servant,” who was mostly likely Matte.

The Will of James Browne, dated 1694, bequeathing “Matte my negro unto my son Jabez” upon the death of wife Lydia.

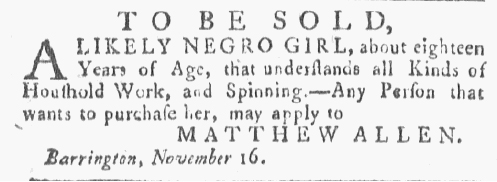

Slavery continued in Barrington throughout the eighteenth century. The 1774 census documents a population of 601, with 57 enslaved peoples, including 18 people listed as “Indian.” At least 12 enslaved people from Barrington, including Scipio Freeman, fought for their freedom during the Revolutionary War with the First Rhode Island Regiment. Scipio Freeman survived the war and gained his freedom. Scipio is buried in the Allin Yard Cemetery in Barrington, and his grave is marked with a lone headstone amidst a field of unmarked graves (likely belonging to other enslaved peoples.) The Allin family, for whom the cemetery is named, were also enslavers. A newspaper advertisement from 1771 revels how enslaved peoples in Barrington were treated as property to be bought and sold. Matthew Allin (a.k.a., Allen) advertised an 18-year-old “likely negro girl,” who knew “all Kinds of Household Work, and Spinning” for sale.

Providence Gazette Newpaper (1771)

By the turn of the nineteenth century, slavery had slowly begun to decline in Barrington, and the 1830 census lists just one enslaved person in the home of Ada Smith. By 1840, 9 “Free Colored Persons” were recorded as living in Barrington homes with a “White” head of household. This raises questions on the lived reality of freedom, as some were likely living in the homes of their former enslavers.

Monument at Prince’s Hill Cemetery

In 1903, Barrington sought to recognize the formerly enslaved peoples of the town and dedicated a memorial to the “negro slaves and their descendants who faithfully served Barrington Families.” The memorial made national news, and the New York Times described it as the first memorial in the U.S. to “negro slaves.” The memorial still stands today in Barrington’s Prince’s Hill Cemetery. In contrast to the Prince’s Hill marker, the Rhode Island Slave History Medallion in Barrington formally acknowledges the enslaved peoples of Barrington in their own right.

To learn more about slavery in Barrington, please visit the Barrington Preservation Society website: https://barringtonpreservation.org.

Reference Sources

MONUMENT TO NEGRO SLAVES.: First Memorial of the Kind in This Country Erected at Barrington, R.I. New York Times (1857-1922); Jun 15, 1903; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times, Page 3.

Address At Dedication Of Memorial Monument To The Negro Slaves Of Barrington, R.I., June 14, 1903. Hon. Thos. W. BicknelI., A. M. I.L. D., Ex-Commissioner Of Public Schools, Rhode Island. The Colored American Magazine. September 1903, Page 628.

Rhode Island Colonial Census of 1774, James Brown, Barrington, Rhode Island, British America, Ancestry.com, Page 236

Findagrave.com/memorial/19136823/james-brown

Probate Records 1687-1916; Index 1687-1926; Author: Bristol County (Massachusetts); Register of Probate; Probate Place: Bristol Massachusetts. James Brown, ancestry.com/imageviewer/cpllections/9069/images/0461882-00315

Bristol County (Mass.) Probate Records 1690-1916; Index 1687-1881 [Bristol County Massachusetts]; Author; Massachusetts Probate Court (Bristol County); Probate Place: Bristol Massachusetts. Lydia Brown, ancestry.com/imageviewer/cpllections/9069/images/0571358-00782

A History of Barrington, Rhode Island, Bicknell, Thomas Williams, Snow & Farnham Printers, 1898

Mister Myles His Negro No Hope of Life, In American History, Yalebooks.com, John G. Turner, April 13, 2020

John Myles, the early New England Baptist, and Liberty, Patheos.com/Blogs/Anxiousbench; John Turner, January 17, 2019

In A Place Called Swansea; John Raymond Hall, Gateway Press, Inc., 1987

Captain Thomas Willett First Mayor of New York, New York History, Vol.21, No. 4, pp. 404-417; Elizur Yale Smith; Cornell University Press, October 1940

Soldiers in King Philip’s War, A Critical Account of That War; George Madison Bodge, A.B., Published By Author, 1896

Notes for Immigrant-Capt. Thomas Willet; Will and Inventory of Thomas Willett, 1674; Ancestry.com

Sowams with ancient records of Sowams and parts adjacent; Bicknell, Thomas Williams;

Associated Publishers of American Records, New Haven, Conn. 1908.

The Will of Rev. John Myles: “Massachusetts, Plymouth County, Probate Records, 1633-1967,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G97D-V3CL?cc=2018320&wc=M6BX-F29%3A338083801 : 20 May 2014), Wills 1633-1686 vol 1-4 > image 549 of 616; State Archives, Boston.

The Will and Inventory of Thomas Willet: “Massachusetts, Plymouth County, Probate Records, 1633-1967,” images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-997D-V3LL?cc=2018320&wc=M6BX-F29%3A338083801 : 20 May 2014), Wills 1633-1686 vol 1-4 > image 364 of 616; State Archives, Boston.

Forgotten Patriots, African American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War; Eric G. Grundset, Editor and Project Manager; National Society Daughters of the American Revolution; 2008

The Name of War, King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity; Jill Lepore; Vintage Books division of Random House, Inc., New York; 1998

Atlantic History; Trevor Burnard, Editor in Chief; https://www.oxfordbibliogr