By Catherine W. Zipf, The Bristol Historical & Preservation Society

The Early Years of Slavery in Bristol

In the wake of King Philip’s war (1675-78), the spiritual and political center of the Pokanoket tribe known as Potumtuk (Mount Hope) was confiscated by Plymouth Colony as a war prize. At this time, many Indigenous Peoples living in the area, some of whom had fought in the war, were sold into slavery in the West Indies. In 1680, Plymouth Colony sold the land to four founding proprietors, who laid out the town of Bristol on the east side of Potumtuk’s peninsula.

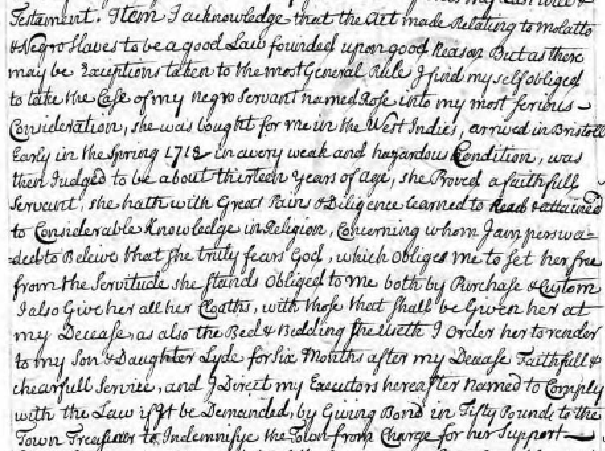

Excerpt from the will of Nathaniel Byfield, 1732. Courtesy of the East Bay BIPOC Research Committee.

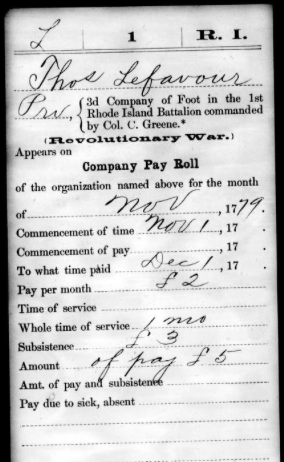

Even in its founding years, the town’s population included enslaved African and Indigenous people. In 1718, Town Founder Nathaniel Byfield purchased a 13 year old girl named Rose, who had just been brought to Bristol from the West Indies (proving a “faithful servant”, Rose was freed in Byfield’s will in 1732). Merchant Joseph Greenhill owned four enslaved people, London, Angura, Adjuba, and Primo (they were also freed in Greenhill’s will). On the eve of the American Revolution, Bristol was home to 132 enslaved people (115 of African descent, 17 of native descent), which represented 11% of the town’s population. Four of them, Plato Van Doorn, Thomas Lefavour, Prince Ingraham, and Juba Smith, fought with the First Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution.

Military payroll card for Thomas Lefavour for the month of November 1779. Courtesy of the East Bay BIPOC Research Committee

After the Revolution, Bristol’s elite families embarked on an intensely profitable period of human trafficking. Most famous among them were the DeWolfs, but other families, including the Wilsons, Fales, Ushers, Wardwells, and Munros, also participated in the slave trade and in the manufacture of slave-related goods. Ships sailing to Africa required captains and agents, as well as goods and provisions purchased from merchants, blacksmiths, coopers, carpenters, tradesmen, and farmers. Almost everyone in Bristol found ways to profit from human trafficking, including through investments in local banking and insurance institutions or through the purchase of slave-produced commodities, like sugar and coffee. Bristol remained a central hub of such activities long after the 1807 embargo outlawed the trade in enslaved peoples.

The DeWolf Warehouse and Wharf

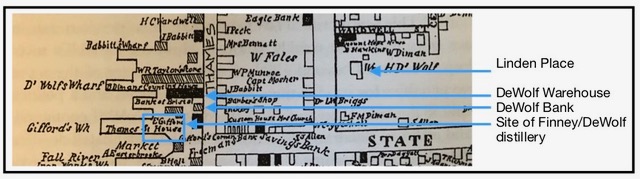

Distilling was a key activity in Bristol’s economy. Prior to the American Revolution, Jeremiah Finney constructed a rum distillery on the wharf at the corner of State and Thames Streets. In 1795, Jeremiah’s son, Josiah, sold the distillery to James and William DeWolf, who had married Josiah’s daughter, Charlotte. This property became the epicenter of the DeWolf family’s slave trade empire.

Map dating to 1850 showing an early configuration of the DeWolf Wharf. Courtesy of the Bristol Historical & Preservation Society.

Shortly after purchasing the wharf, the DeWolfs constructed a store and a bank on its Thames St. side. In 1801, they built another “large brick store” immediately to the north of the bank and enlarged Finney’s distillery to contain 18 circular vats and a stillhouse measuring 78 by 48 feet. The distillery consumed 120,000 gallons of molasses per year and employed three men. Unfortunately, because the size of the still is unknown, the amount of rum produced each year cannot be calculated, but clearly the output was considerable.

The DeWolfs used the rum and the proceeds of its sale, both locally and abroad, to expand their operations. While documents show that the warehouse was completed by 1818, construction probably started earlier. Many stones did, indeed, come from Africa, and most likely were worked into the warehouse as they came, rather than piling up on the wharf. One imagines the idea to do this was something of an inside joke, as the symbolism of African stones being used to construct a building to house African enslaved people and the products they produced is too obvious to be otherwise.

Over time, the DeWolf family was responsible for financing, in whole or part, 88 slaving voyages, which accounted for nearly 60 percent of all African voyages that originated in Bristol. They also brought an estimated 30,000 kidnapped and captured Africans to Cuba, the West Indies and the American South. Unlike other slave traders, the DeWolfs took orders from other Bristol residents for enslaved people and usually delivered them directly upon arrival. Thus, while it did house a handful of enslaved people, more often, the warehouse was used to store commodities.

The Decline of Slavery in Bristol

In 1825, the over-leveraged George DeWolf went bankrupt. His sugar crop had failed, preventing him from repaying loans to creditors around the world. During a December snowstorm, he and his family took what they could carry and traveled to George’s plantation in Cuba, called “Noah’s Ark”. George’s substantial debts caused a cascade of defaults around town and led to a years-long depression. Even the DeWolfs struggled through the next few decades.

The Maria Hazard House (left) in the New Goree neighborhood of Bristol, RI. Courtesy Catherine W. Zipf

George DeWolf’s bankruptcy heralded the end of the era of enslavement in Bristol; the 1820 census is the last to document any enslaved people in Bristol. But, things were far from equal for people of color. By 1830, Bristol’s African-American and Indigenous community, consisting of the descendants of enslaved people owned by families like the DeWolfs and Munros, had found a home in New Goree, located on Wood Street between State Street and Bay View Avenue. Many continued to work in the homes of Bristol’s elite families in relationships that paralleled the era of enslavement. Others found work in the developing rubber industry. With new opportunities generated during the post-Civil War climate, many of Bristol’s African-American families began to move elsewhere. By 1920, with only a handful of such families remaining, Bristol had largely forgotten this important part of its history.

Further Reading

Stephen Chambers, No God But Gain: The Untold Story of Cuban Slavery, the Monroe Doctrine, and the Making of the United States. US: Verso, 2015.

Christy Clark-Pujara, The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island. New York: NYU Press, 2018.

Cynthia Mestad Johnson, “From Bristol to the West Indies and Back: James DeWolf and the Illegal Slave Trade”. Rhode Island History: The Journal of the Rhode Island Historical Society, Vol. 78, No. 2, Spring 2021.

Cynthia Mestad Johnson, James DeWolf and the Rhode Island Slave Trade. US: The History Press, 2014.

Nancy Kougeas, “Building the San Juan Plantation: A Bristol Family in Cuba, 1818-46”. Rhode Island History: The Journal of the Rhode Island Historical Society, Vol. 78, No. 2, Spring 2021.

Rafael Ocasio, A Bristol, Rhode Island, and Matanzas, Cuba, Slavery Connection: The Diary of George Howe. US: Lexington Books, 2019.\

Charles Rappleye, Sons of Providence: The Brown Brothers, the Slave Trade, and the American Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007.

Catherine W. Zipf, “Finding Hope in “New Hope”: George Howe’s Diary of Life on a DeWolf-Owned Plantation in Cuba”. Rhode Island History: The Journal of the Rhode Island Historical Society, Vol. 78, No. 2, Spring 2021.