Jamestown Slavery

Peter Fay, Jamestown Historical Society

Figure 1– Jamestown (Conanicut), R.I. – Blaskowitz Map, 1777

Jamestown, Rhode Island, comprising the islands of Conanicut, Gould and Dutch, lays in the center of Narragansett Bay, occupying, since colonial times, a special place as a crossroad for commerce and transit across southern New England. Along with trade and travel, slavery also tread this path through Jamestown during almost two centuries. The town, not coincidentally, is a neighbor to Newport, the originator of the largest number of American-owned slave voyages in the nation.

The Foundation of Slavery

The institution of slavery permeated every facet of Jamestown’s daily life from the European settling of the town in 1657 into the early 19th century. Even before Africans were brought to the island, indigenous inhabitants of Conanicut were captured and enslaved. In 1638, Roger Williams wrote that Narragansett sachems protested two of their women being “carried away in an English ship from Conanicut.” Indian enslavement became ingrained in the colony across generations, and in 1676, Governor Caleb Carr, a Jamestown landholder, paid twelve bushels of Indian corn to purchase “an Indian captive” taken prisoner in the King Philip’s War. When the governor died two decades later, he bequeathed to his son Edward one-hundred fifteen acres on Conanicut, his interest in Dutch Island, and “my Indian boy Tom.”

The Expansion

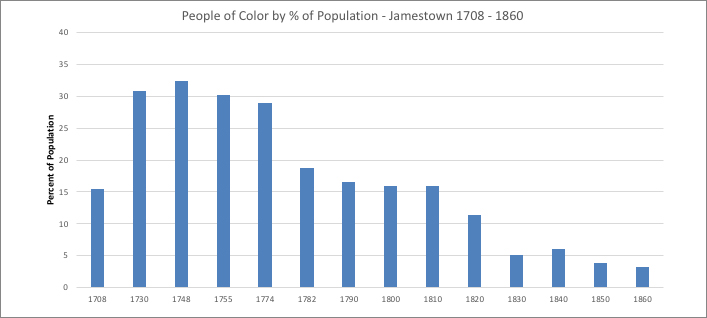

On the island there grew a community of newly arrived West Africans, second-generation African Americans, and Native Americans, who were mostly enslaved and peaked in size at over one-hundred sixty in 1774. But many hundreds of slaves called Jamestown home over the centuries and most were laid to rest in the town Common Burial Ground or on farms, yet not one grave marker commemorates their existence today.

Figure 2 – Black and Indian Population, Jamestown, R.I.

Indian enslavement was soon augmented by the explosion of the Rhode Island slave trade with Africa. Various prominent Jamestown residents financed, captained, and provisioned slave voyages, and purchased the enslaved cargo upon their return.

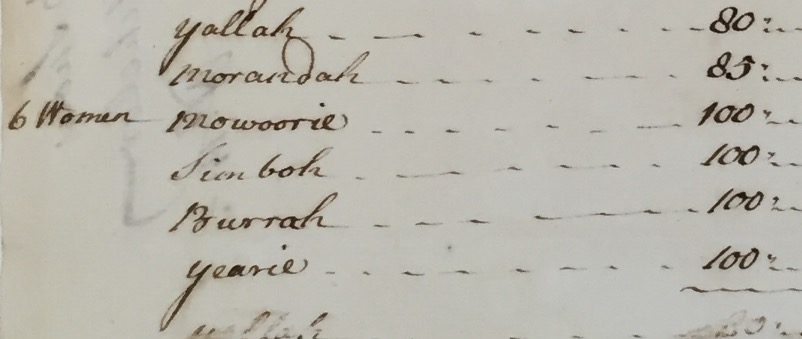

“One Negro Woman”

For example, the Carr family of Jamestown once again sought out enslaved labor for their vast estates. In 1743 Sayles Carr, grandson of the governor mentioned above, purchased at a slave auction at Hassey’s “Green Dragon” coffee shop in Newport “one Negro woman… £105.” She had disembarked from the slave ship Jolly Bachelor, owned by famous Boston merchant Peter Faneuil, for whom Faneuil Hall, visited today by millions of tourists each year, is named. Court records reveal she was one of six women on the ship. Their African names were Yallah, Morandah, Mowoorie, Simboh, Burrah, and Yearie, which are Temne and Mandinka names common to Sierra Leone on the west coast of Africa, and to Rio Pongo, Guinea, to the north.

Figure 3 – African names and appraisal (in pounds) of six women aboard the Jolly Batchelor, R.I. Admiralty Court, 1743.

Baby Hannah

Slavery in Jamestown grew not simply by purchases, but also through births. David Greene was a Quaker farmer and, for a time, owner of the Newport-bound ferry; his home, the Greene Farmhouse, still stands on Shoreby Hill. In 1723 he signed a bill of sale to “put and bound his slave named Hannah, being a Girl half Indian and Half-Negro and about one Year and six months old, [to be] a servant and Apprentice unto George Mumford of South Kingstown” for 19-1/2 years. Hannah’s mother is nowhere mentioned.

Resistance to Slavery

Slavery did not define enslaved people nearly as much as their masters may have hoped or believed. Enslaved men and women resisted, bargained, fought, fled, and used every available opportunity to direct their own destinies.

Hannibal

Hannibal, an enslaved African American in North Kingstown, had a well-documented history of refusing to buckle to authority. His owner, Reverend James MacSparran of North Kingstown, called him “headstrong and disobedient.” Hannibal repeatedly fled his owner to other Narragansett plantations, apparently flouting his “gift of chastity,” prompting MacSparran to ask the blacksmith to have “pothooks put about his neck” (an iron collar with protruding bars), and later to “expose him to the whip.” Apparently, none of this subdued Hannibal, as a week later he was overheard “concocting another escape,” so in 1751 MacSparran sent him to be broken by John Martin in Jamestown.

Martin, a close friend of MacSparran, had a particular advantage over his mainland friend. The 1715 “Act to Prevent Slaves from Running Away from their Masters” forbade ferrymen to “Carry, convey or transport, any slave… over any ferry… without a certificate” of their master. For slaves, Jamestown was an island prison. In addition, Martin’s son happened to be the ferryman at West Ferry and slave-holder David Greene, owner of Hannah, was ferryman at the East Ferry. Despite this supremacy of control, Hannibal seems to have remained indominable, as his owner apparently gave up and later ordered Martin to sell him. Sale was a dreaded fate, especially if Hannibal was sold, as was common for intractable slaves, into the West Indies where slaves died young.

With the turmoil of the Revolution, came many opportunities for self-determination, though not always in expected ways. Many slaves fought in the War of Independence. Many others sought refuge and freedom behind British lines.

Jenny Carr

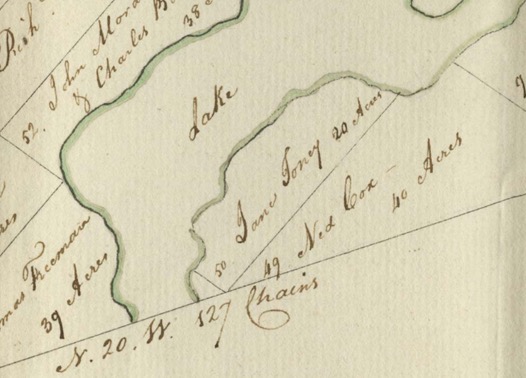

Jenny Carr was owned by Daniel Underwood at the Underwood farmhouse, which foundation can still be seen on East Shore Road. She married a Black seaman and privateer, Lango Toney, who had been a crewman on the privateer Defiance in the French and Indian War.

She became free through purchase, perhaps by her husband, and carried as proof her own bill of sale. Now named Jenny Toney, she left her former owner on the island, moving to Newport in 1774 with two others, likely her daughters. She found refuge amongst the runaway slaves flocking to the British lines during the War of Independence, after slaves of rebelling owners had been promised freedom if they joined the British.

Toney fled Newport when the British withdrew to New York in 1779. From there she and her daughter Judith Weeden embarked with loyalist refugees on the ship L’Abondance in 1783, bound for British territory in Nova Scotia. She joined 3,500 other freed Blacks, many of them runaway slaves, from the North and South, including Harry Washington, who had escaped from his master, General George Washington of the Continental Army. Jenny Toney at 52 years of age was now not only free, but a landholder, given twenty acres of land by the British crown to settle with her daughters Judith, 15, and Patience, 23, in Birchtown, Nova Scotia.

Figure 4 – Jane (Jenny) Toney Land Grant – 20 acres, Birchtown, Shelburne, Nova Scotia, 1787

Other enslaved Jamestowners leveraged other opportunities to their advantage.

Jabez Remington

Jabez Remington was born in Jamestown in 1759, a slave of Benjamin Remington (1733-1820), a deputy from Jamestown in the General Assembly who is buried in the Jamestown Common Burial Ground.

Jabez Remington became free upon joining the 1st Rhode Island Regiment at age nineteen during the War of Independence. However, like all slaves enlisting in the “Black Regiment”, his was not an act of free will nor a magnanimous act of his master, but rather a financial compact between buyer and seller, the slave being the object of exchange. The rebel government of Rhode Island purchased soldiers to bolster their flagging military recruitment.

Jabez Remington was delivered to Captain Dexter’s company of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment by his owner on March 15, 1778. His enlistment record noted his “black complexion with black hair.” He was “appraised and valued at £120” by the General Assembly, who then paid his owner.

Jabez Remington fought in the battle of Rhode Island in 1778, in a brutal fight on Butt’s Hill in Portsmouth, having no battle experience, minimal training, and meager equipment. Despite this, the Americans retreated in order, and the Black Regiment of 125 lost only three men.

Records of Remington’s remaining years in the war are sparse, but they were certainly filled with severe deprivation and hardship, often with insufficient food, clothing, and shoes. He likely participated at a battle in Croton River, New York, where Colonel Greene was “cut to pieces” in a loyalist attack. Later, in the Battle of Yorktown, Virginia in October 1781, the Rhode Island Regiment played a significant role, quickly storming Redoubt No. 10 while their Captain Olney took a bayonet to the stomach, almost dying. Later he marched on a final expedition in the bitter February winter of 1783 to Oswego, New York in a failed attempt to take Fort Ontario. He lost five toes from frostbite and was honorably discharged with a pension for invalids of one pound, ten shillings per month.

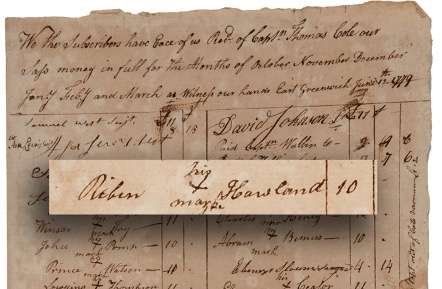

Robin Howland

Another Jamestown soldier came from Jamestown’s Howland farm. The Howlands descended from Job Howland, a Quaker yeoman whose estate was inventoried in 1763. The beds in the chamber were appraised at £670, and “in the kitchin, 1 Negro boy named Robin, £1000.” This enslaved boy Robin and another named Dick were inherited by John Howland.

When the colonial government evacuated livestock from Conanicut Island to prevent it from becoming provisions for the British, the Howland household moved temporarily to Warwick.

Figure 5- Mark of Robin Howland – military company Payroll June 12, 1779

Robin Howland mustered with Captain Thomas Arnold’s all-Black and Native American company in Colonel Greene’s 1st Rhode Island Regiment, and within weeks found himself in pitched battle in Portsmouth in the American lines along with Jabez Remington. Later, he too marched to Yorktown, Virginia and took part in the final battle of the war.

Months after victory, with poor hygiene and cramped quarters, disease spread across the camps. Forty-three Rhode Island Regiment soldiers died in December 1781, including Robin Howland who died in Yorktown of an unknown illness and was buried there.

The Jamestown Town Council was well aware of Howland’s sacrifice. A decade later, in April 1792, it voted to appoint an administrator for the estate of Robin Howland, “a Negro man that once belonged to Mr. John Howland and enlisted into the Continental Service in Colonel Greene’s regiment and there deceased.” A century later the council would name Howland Avenue in the center of town after the slave-holding family, but the slave who gave his life would go unhonored and unremembered until now.

Dick Howland

While Robin Howland’s fate is now known, Dick’s is not. While John Howland was in Warwick with his slaves in 1777, there appeared an advertisement in the Providence Gazette warning of a “Mustee” (Black and Indian heritage) runaway:

“Run away from the Subscriber, a Mustee Slave, about five feet six inches high, about 20 years of age…. Whoever will apprehend said slave, and secure him in any jail within the United States, and give Notice or deliver him to his Master, shall receive Five Dollars Reward, and all necessary charges, paid by John Howland. Warwick, April 7, 1777.”

Dick Howland, however, was never heard from again.

The End of Slavery

Slavery in Jamestown experienced a very slow demise.

Rhode Island outlawed any new enslavement in 1784 but left existing slaves in bondage for the rest of their lives, unless manumitted by or purchased from their owner by the slave’s family members. While a handful of slaves were manumitted, it took Jamestown almost half a century more to free all its slaves, many dying still in bondage.

Since towns were required at their own expense to provide support for the poor, in the aftermath of the war, the town renewed efforts to rid itself of “undeserving” poor or simply anyone who required public financial support. Black and indigenous people, enslaved or free, were especially targeted.

Sarah Warwick and Mary Primas

Dozens were “warned out” of town, such as Sarah Warwick and Mary Primas (alias Bristol), “two Negro women residing in this town not being inhabitants.” Failing to leave, in 1788 they were ordered “out of Jamestown… to the towns where they belong, if they return they are to receive ten stripes upon their naked backs.” When Rose Weeden, a Black woman enslaved by Nicholas Carr, was convicted of stealing pork, the penalty was “twenty stripes upon her naked back.” She then became “destitute of a house and every other necessary and support of life and has been forbidden entrance to her said master’s house.”

10-year-old Boy Jamestown

Black enslaved children who might require town funds for support were put under extra scrutiny. In 1784, the same year the much-heralded Gradual Abolition act was passed, the Town Council ordered a bill of sale of “a certain Negro Girl” owned by Rebecca Martin. Rebecca Carr Martin had inherited slaves from her husband’s father, John Martin (owner of Hannibal) who had owned ten slaves before the war, and she failed to provide for their support. By 1791, the Town Council had taken over management of widow Martin’s slaves altogether, as she was in “want of prudent management of her estate” and her slaves are “likely to become chargeable to the town.” The council appointed themselves guardians, ordered her to “transact no kind of business whatsoever,” and promptly dispatched her “Negro woman named Dinah,” her five children”, and three more of her slaves into indentured servitude. On the holy day of Christmas Eve, 1791, Martin’s ten-year-old boy “Jamestown” was sold by the council for $30 into indentured servitude. After eleven years, at age twenty-one, the boy would be released with “some clothes” in return for his labor.

The councilors, who were from the Howland, Carr, Eldred and Hammond families, were or had recently been slaveholders themselves.

Even as slavery waned, the town continued to use bondage as a threat. It ordered formerly enslaved Black people, especially women, keeping “disorderly houses” to appear before the town council. The punishment for this crime was indenture, authorized by the 1770 “Act for the Breaking Up Disorderly Houses,” which forbade “free negroes and mulattoes” to have “disorderly houses” or entertain slaves at “unreasonable hours or in an extravagant manner.”

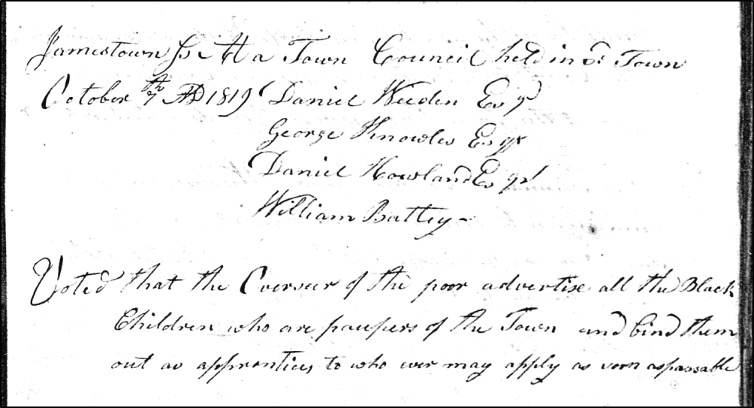

Figure 6 – “Advertise all the Black Children who are paupers… and bind them out… as soon as possible.” (Town Council, 1819)

In 1819, the Town Council, again employing race to the town’s financial advantage, urgently ordered “the overseer of the poor advertise all the black children who are paupers of the town and bind them out as apprentices to who ever may apply as soon as possible.” Among the councilors issuing the order was Daniel Howland, owner of James Howland, still enslaved thirty-five years after passage of the Gradual Emancipation Act.

James Howland

James Howland remained at the white Howland household until his death, even after he finally gained his freedom. In his will in 1837, Daniel Howland ordered the now-free “old Black man James to be supported out of my Real Estate as long as he lives.” James Howland died in 1859, still a servant at the Howland mansion after 100 years, the last living person who had been a Rhode Island slave.

Bibliography

Bartlett, John. Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Vol IV, 1707-1740. Providence: Providence Press Co., 1865.

Bartlett, John. Records of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Vol. X, 1784-1792. Providence: Providence Press Co., 1865.

Bicknell, Thomas W. The history of the state of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations New York: American Historical Society, 1920.

Carleton, Guy. 1st Baron Dorchester: Papers, (PRO 30/55/100) 10427, The National Archives, Kew, England.

Carr, Edison. The Carr family records. Rockton Ill: Herald Printing House, 1894.

Donnan, Elizabeth. Documents illustrative of the history of the slave trade to America, Vol. III. Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1930-35.

Jamestown Historical Society Archives, https://jamestownhistoricalsociety.org/online-catalog/, accessed 10/21/2020.

Jamestown Town Records, Town of Jamestown, Rhode Island

MacGunnigle, Bruce C. Regimental Book, Rhode Island Regiment for 1781, etc. East Greenwich, RI: R.I. Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 2011.

MacGunnigle, Bruce. “1777 Military Census, Warwick, Rhode Island”, Rhode Island Roots, Vol. 10 (1984).

MacSparran, James. A letter book and abstract of out services, written during the years 1743-1751. Boston: D.B. Updike, 1899.

NARA Microfilm M247, Papers of the Continental Congress

North Kingstown Town Records, Town of North Kingstown, Rhode Island.

Rhode Island Census, 1774, Jamestown, Rhode Island.

Rhode Island Historical Society Archives, Robinson Research Center, Providence, Rhode Island.

Rhode Island, Acts and Resolves at the General Assembly 1747-June 1776. Providence: 1775-1776.

United States Census, 1790, Jamestown, R.I.

Williams, Roger. Complete Writings of Roger Williams, Vol. 6. New York: Russell & Russell, 1963.