By Robert Geake and Fred Zilian, Ph.D.

The Battle of Rhode Island

On this site during the War of Independence in 1778 an event occurred unlike any other in North America – local slaves, purchased by the rebel Rhode Island Assembly, fought alongside free white, Native American and African American soldiers against British-Hessian forces.

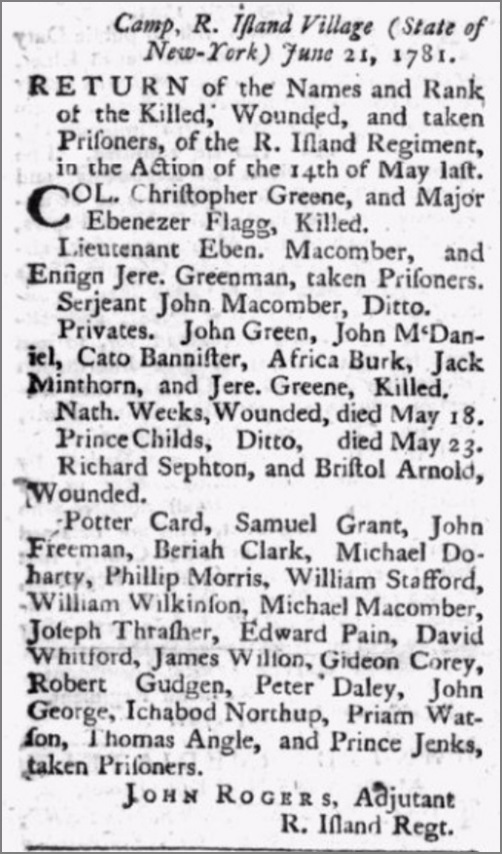

Privates Ritter Gardner of Exeter, Prince Brown of Providence, and Ichabod Northup and Caesar Updike of North Kingstown had only months earlier been property of their masters, enduring generations of enslavement. Yet now, in August, they and over eighty other slaves stood armed and trained by the emergent rebel government that purchased them for between £30 and £120 apiece. It promised them freedom for their voluntary service and placed them shoulder to shoulder with five thousand other American rebel troops facing the highly trained British and Hessian troops advancing from the south of the island.

They were part of the small contingent of two hundred twenty-five, named the “First Rhode Island Regiment”. They sometimes were known as the “Black Regiment” – an imperfect description, since some were Native Americans and one-quarter were white officers. The privates included slaves purchased from their masters by the rebel government, free African Americans, Native Americans, and some whites. However, in this unique regiment, races were segregated by company, unlike others in New England which integrated free people of color. For one day in August, the combined New England regiments successfully defended this ground, repelling three assaults by the British-Hessian forces allowing an orderly retreat from the superior British forces.

The British forces had been quartered on Aquidneck Island since 1776. With the arrival of the French Navy in August 1778 in Narragansett Bay, American forces had briefly moved onto the island to support the expected French advance. However, after sustaining great damage from a hurricane, France withdrew to Boston, and rebel forces began to retreat from Aquidneck.

By August 29, with militia leaving and men growing ill from the foul weather and humidity, the American forces had declined to about 7,800 men. British-Hessian forces totaled about 6,000 soldiers and marines. The enemy line ran west to east across Portsmouth from Quaker Hill to Turkey Hill to Almy Hill. The forces on the western flank were mostly German regiments and they faced, among other units, the 1st RI Regiment.

The regiment had been formed after a proposal by Rhode Island general James Mitchell Varnum that a battalion of slaves be enlisted to fight for Rhode Island. The officers of the battalion would be white, and the enlisted slaves would earn their freedom after at least three years of service. The Act creating the regiment was passed by the General Assembly in February 1778. Col. Christopher Greene was sent with other officers back to his home state of Rhode Island to recruit men for the 1st Rhode Island. While the regiment enlisted eighty-nine slaves initially, the remainder of the regiment was filled with free indigenous and black men who enlisted, as well as about eighty-five whites.

Washington appointed Greene commander, and the men trained for the next six months in East Greenwich, often parading before spectators who came out to see the soldiers of this mixed race battalion.

Commanded on this day of the battle by Maj Samuel Ward, the regiment was situated behind a “thicket in the valley,” which gave them a strong defensive position. They also used the stone walls in this area as defensive positions from which to fire on the advancing troops. The Regiment had the primary responsibility for holding an important fortification on Durfee’s Hill, now called Lehigh Hill.

Three full assaults by Hessian forces failed to break the line defended by four Continental regiments and the 1st Rhode Island. All the while Hessian cannon were firing on them from Turkey Hill. In his diary, one of the Hessian commanders, Captain Friedrich von der Malsburg, noted that during these assaults, “they found large bodies of troops behind the works and at its sides, chiefly wild looking men in their shirt sleeves, and among them many Negroes.”

In seven hours of combat that day, the American line held. This allowed for the successful retreat and evacuation of General Sullivan’s Army to Tiverton across the Sakonnet River. Regarding casualties, Gen Pigot’s official report stated combined British, Hessian, Loyalist casualties of 260 with 38 killed. Gen Sullivan reported casualties of 211, with 30 killed.

Assessment of the Battle

Tactically, the battle is considered a draw. Neither commander wanted a full-scale battle. British Gen Pigot was happy to push the American force off the island. He had no desire to risk his military force or Newport for a chance to gain a decisive victory. General Sullivan was happy to withdraw his force intact off the island before the British reinforcements arrived.

Strategically, most historians would call the entire campaign a win for the British. They were not captured or pushed off the island. They remained another 14 months until they decided to end the occupation in October 1779.

Nonetheless, this was the first time that American and French forces had planned an allied military operation, one they would have executed, but for the hurricane. Finally, it was the largest battle of the war in New England and the last significant battle in the northern theater.

The Black Regiment

Also largely lost to history was the significance of the “black regiment”. Once aligned with the 2nd Rhode Island Regiment in January 1780, it then became a fully racially integrated regiment in the Continental Line. Their contributions to American victory, particularly at Yorktown, have only recently been acknowledged.

A monument to the Black Regiment now stands in Patriots’ Park, Portsmouth, and is dedicated to the “first black slaves and freemen who fought in the Battle of Rhode Island as members of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment.”

Members of this regiment exhibited great courage on the battlefield as well as during expeditions undertaken by American forces during the course of the war. As freemen after the war, some of those former slaves who had enlisted established themselves successfully in communities throughout Rhode Island. Many more however lived in destitution, eking out a living at the lowest rung, or relying on charity since pensions took 40 years to arrive – often too late.

The Soldiers

Ruttee Gardner was sold to the Assembly on May 8, 1778 for £30 by Nicholas Gardner of Exeter – the smallest amount for any recruited slave. He served in the regiment with Capt. Lewis’ company. He appears to have served out his time with the regiment and likely was injured or became ill during his time of service. He is listed as “sick in North Kingstown in March of 1779 and was honorably discharged from service in April of that year. His illness or injuries seem to have continued to plague him, for on March 28, 1785, Hezekiah Babcock submitted a bill to the town of Hopkinton for the “boarding and nursing of Rutter Gardner, a negro man who formerly belonged to Nicholas Gardner of Exeter, and a late soldier in the Rhode Island Continental Regiment”.

Prince Brown was a slave owned by the Brown family of Providence, founders of Brown University. Joseph Brown and cousin Nicholas Power discovered their slave Prince had legally enlisted in the 1st Regiment under Col. Christopher Greene. Amidst the height of public denunciations of British usurpation of American freedom, the two owners immediately petitioned and persuaded the General Assembly to “resolve that a negro man Prince belonging to [them]… be discharged from the said regiment.” He was returned to slavery on their farm in Grafton, Massachusetts.

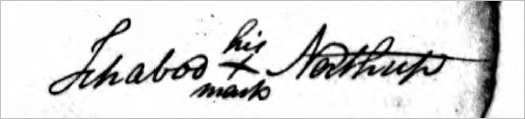

Ichabod Northup of North Kingstown was sold to the Assembly for £120 by one of the Northups of North Kingstown. The slave master’s homestead still stands on Featherbed Lane in that town. Ichabod not only fought in the Battle of Rhode Island but also at Croton, N.Y. when attacked by loyalists who killed Col. Greene. He was captured, threatened with hanging for not divulging troop movements to the enemy, and spent the remainder of the war a prisoner. He returned after the war to East Greenwich, purchasing a house on Division Street which still stands today. In 1820 he testified that he relied on charity, was unable to work, his toes having frozen in the war, was “impoverished”, and “could not support himself” and family, and his house was “much out of repair”. Later his son campaigned to desegregate Rhode Island schools, while a grandson and great-grandson fought in the civil war.

Caesar Updike was sold for £120 by Lodowick Updike, one of the wealthiest landowners in Kings County. He served under Colonel Christopher Greene, earning an “Honorary Badge of Distinction”, given to soldiers serving “at least three years with bravery”. After being furloughed in June 1783, he returned and in 1795 was working at Smith Castle in North Kingstown as a wage laborer for the Updike family – his former owners. He was paid in corn, shoes, and sometimes currency. By 1800 he was in East Greenwich, finally receiving a pension in 1818 and died a year later.

London Hall was 40 when he enlisted in 1778 in Capt. Dexter’s Company for three years. However, in 1790 his former master, William Hall of North Kingstown, claimed he has never been appraised for his value before enlisting, and demanded his re-enslavement or £80. Luckily by 1790 the legislature considered his required three years’ service sufficient for his freedom and dismissed the claim.

The Legacy

Many members of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment faced hardship after the war, but their legacy would be left for the generations to come who continued the fight for freedom that they began. They took the first ground in the long battle for their people—black and indigenous—to change the landscape of America to reflect the promise that lies within its Declaration of Independence, that all are created equal and have the inalienable right to “life, liberty. and the pursuit of happiness”.